Research

commonsense consent

Legal scholars and philosophers often say that consent is normatively significant because it constitutes an expression of autonomous will. Consent is rendered invalid by factors that compromise autonomous decision-making, such as coercion (undermining freedom), incapacity (undermining competence), or deception (undermining knowledge).

That’s what experts believe, but how do ordinary people understand consent? In a series of psychological experiments, I find that people largely see coercion and incapacity as consent-defeating, but they feel differently about deception. A substantial proportion of survey respondents believe that morally valid consent can be granted despite the presence of significant and wrongful deception. Their intuitive judgments thus defy the prevailing legal and philosophical understandings of consent. I use this empirical discovery to revisit the so-called “riddle of rape-by-deception” and to interrogate the relationship between public attitudes, normative theory, and law.

A nontechnical summary of the paper is here. The full paper is here. Read my New York Times op-ed summarizing the findings here. You can listen to the Yale Law Journal editors interview me about the paper here.

How do we judge the voluntariness of consent?

“Before we begin the study, can you please unlock your phone and hand it to me? I’ll just need to take your phone outside of the room for a moment to check for some things.”

Would you agree to this request, if you were a participant in a psychology study? Would a reasonable person? How difficult would it be for a reasonable person to say “no” to the researcher?

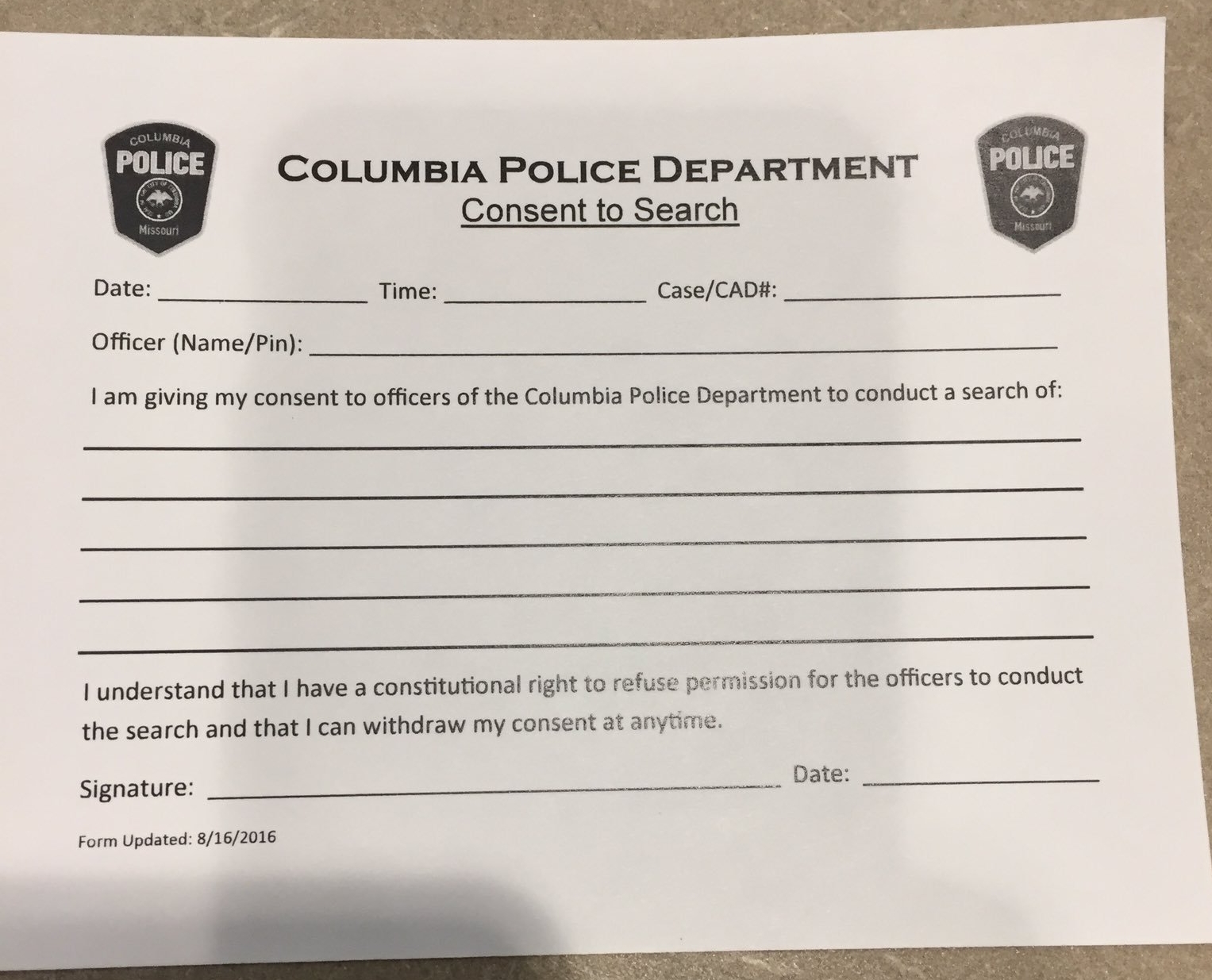

Vanessa Bohns and I conducted a series of laboratory studies in which participants were approached with this script. We found that whereas the vast majority think a reasonable person would refuse to hand over their phones, almost no one turns us down when we actually ask them. Predicted compliance is low (14%), whereas actual compliance is high (97%). Moreover, those who actually face the request report feeling significantly less free to refuse than those who contemplate the same situation hypothetically. Further testing shows that advising participants of their right to refuse the search does not appreciably affect compliance behavior or self-reported feelings of pressure.

The disconnect between what people think they would do and what people actually do matters legally, we argue, because a key inquiry in Fourth Amendment consent search cases is whether a reasonable person would have felt free to refuse the officer’s request to perform the search. We believe that even when external validity concerns are taken into account, our findings suggest that systematic psychological biases undermine our ability to judge the voluntariness of others’ consent. In an Essay published in the Yale Law Journal, we argue that judges tasked with determining voluntariness are likely to understate the degree to which suspects feel pressure to comply with police officers’ requests. In addition, our results suggest that reformers’ efforts to impose Miranda-like warning requirements on police searches are misguided, because such warnings are unlikely to counteract the powerful psychological demands presented by such requests.

A nontechnical summary of the paper is here. The full paper is here. Read our New York Times op-ed summarizing the findings here.

Does the use of consent forms improve the consent process?

In 2018, Bohns and I were awarded an NSF grant to continue studying the psychology of compliance as it relates to search requests. We plan to investigate whether seeking consent via written forms affects requestees’ compliance rates, self-reported feelings of freedom, and knowledge of rights. We will also test interventions designed to help third-party fact-finders make more accurate predictions about how often people comply and how free they feel to say no.

Our preliminary findings suggest that consent forms do little to affect the rates at which people hand over their phones, and may even have a backfiring effect by which they make people feel less comfortable refusing the request.

contract schemas

A growing body of empirical work examines the psychology of contracting. In a review of this literature, I draw on the notion of contract schemas to characterize what ordinary people think is happening when they enter into contractual arrangements. I propose that contracts are schematically represented as written documents filled with impenetrable text containing hidden strings, which are routinely signed without comprehension. This cognitive template, which is activated whenever people encounter objects with these characteristic features, confers certain default assumptions, associations, and expectancies. I argue that contracts schemas supply (i) the assumption that terms will be enforced as written; (ii) the feeling that one is obligated to perform; and (iii) the sense that one has forfeited rights. The picture that emerges from the psychology of contracts literature suggests that laypeople expect the law to find consent in situations where they would prefer it did not, and where it in fact does not.

You can read a draft of the review here. Comments are welcome.

Access to justice: The difference a lawyer makes

The access-to-justice movement aspires to “achieve 100 percent access to effective legal assistance for essential civil legal needs.” Divorce is a quintessential example of the kind of civil legal process that must be made accessible to people who cannot afford lawyers.

The Access to Justice Lab at Harvard Law School has conducted a randomized controlled trial (RCT) evaluating the difference a lawyer makes in obtaining a divorce in Philadelphia County. In an article forthcoming at the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Jim Greiner, Tom Ferriss, Ellen Degnan, and I argue that RCTs are a promising method for measuring court “accessibility.”

Fine Print Fraud

Meirav Furth-Matzkin and I study a common form of deception in consumer contracts: a seller says one thing but the written terms of the contract say another, and the consumer signs the contract in reliance on the seller’s false representation, without reading the terms or noticing the discrepancy. Across several studies, we find that laypeople are rigid contractual formalists: even though they believe it is unfair to hold consumers to terms they were deceived into signing, they nonetheless believe that the law will enforce such agreements as written. In fact, we find that in many cases, laypeople do not give any weight to the fact that the consumer was deceived prior to signing. In an Article published in the Stanford Law Review, we argue that these findings suggest that consumers may be unlikely to challenge contracts induced by fraud, because their formalistic intuitions lead them to believe that they will be held to whatever they sign.

The full paper is here.

A Psychological Critique of the Reasonable Person Standard

I draw on social science research, including my dissertation research, to interrogate the reasonable person standard. I first present the empirical case that fact-finders are inaccurate at determining what behavior is typical in certain situations. Specifically, I argue that fact-finders are likely to overestimate people’s willingness to violate social scripts by acting confrontationally or assertively. I then demonstrate that this social perception bias poses a problem for the reasonable person standard. To the extent that the standard is supposed to compare litigants’ behavior to what an ordinary person would do, the standard is likely to be misapplied by fact-finders thanks to their inaccurate assumptions about what behavior is ordinary. I conclude by proposing a new understanding of what lies “beyond the ken of the jury.”

WHY DO WE HATE HYPOCRITES?

I have long been fascinated by hypocrisy. Why does inconsistency between words and deeds bother us so much? Why is our political discourse dominated by whataboutery and the tu quoque fallacy?

In a series of experiments published in Psychological Science, Jillian Jordan and I, along with David Rand and Paul Bloom, find support for a theory of hypocrisy as false signaling. In a nutshell, it's not that hypocrites fail to practice what they preach; it's that their moralizing earns them reputational benefits that they don't deserve. Take away the reputational benefits, we find, and people forgive the hypocrisy.

This idea of hypocrisy as false signaling makes sense if you think of moral condemnation as a way to boost your reputation. When we scold others for their transgressions, we imply that we ourselves do not engage in such behavior. In our research, we find that people take moralizing commentary—statements such as “it is wrong to eat meat”—as an indication about the speaker’s private conduct. In fact, we find that people would be more likely to infer that the speaker does not herself eat meat if she said, “it’s wrong to eat meat” than if she stated outright, “I do not eat meat.” So moral condemnation functions as a particularly persuasive signal of private moral behavior.

We gain reputational benefits when we speak out publicly on moral issues or chastise others for their moral failings—but those reputational benefits are undeserved if it turns that our private behavior does not align with the signal implied by our condemnation. Hypocrites are disliked, we argue, because their condemnation misleadingly implies that they are good, when their private behavior shows that they are not. Consistent with this theory, we find that hypocrites who don’t signal are liked just fine.

Read the full paper here. Read our New York Times op-ed summarizing the findings here.

BIAS AND POLICE BODY-WORN CAMERAS

In the wake of national outrage and polarization over several high-profile police killings of unarmed citizens, reformers have called for police officers to wear body cameras. In a study of mock jurors’ perceptions of real police footage, I find that observers’ prior attitudes toward the police color their interpretation of what transpired in the videos, resulting in considerable polarization. Further, I find that video evidence does not conclusively outperform non-video testimony in minimizing decision-makers’ reliance on their prior attitudes. Study participants learned of an incident involving a police officer and citizen by either watching a video of the altercation, reading dueling accounts of the altercation written from the perspectives of the police officer and of the citizen, reading a single account from the perspective of a disinterested third party, or reading only the police officer’s version of events. Prior attitudes toward police significantly affected judgments of the officer’s conduct in all four conditions and did not differ significantly across the different types of evidence. Moreover, people who identified strongly with the police—but not those who identified weakly—became more confident in their judgments when presented with video evidence. Ultimately, I believe we should be more skeptical of the commonsense view that body cameras will reduce polarization by telling us unambiguously and definitively what happened.

discrimination in employment: the role of law in shaping attitudes toward outgroups

Sara Burke and I are studying whether attitudes toward minority groups are affected by beliefs about whether discrimination against those groups is legal. We hypothesize that when people learn the outcome of a case involving disparate treatment of a member of a minority group, their feelings of warmth toward the minority group as a whole are affected by whether the judge determines the differential treatment to be legal or illegal. We expect this to be especially true for people who strongly trust the legal system and view the law as having a high degree of legitimacy. In other words, we hypothesize an interaction between perceptions of legal legitimacy and the expressive power of law.